Adult female great white shark

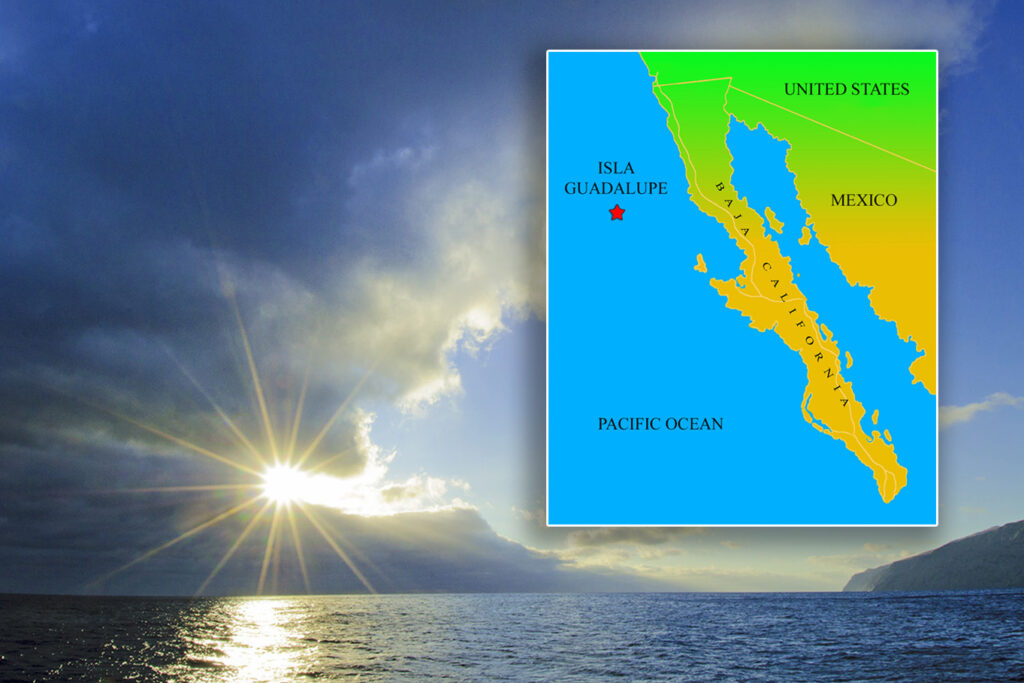

The dramatic cover of Time magazine on June 23, 1975 pictured a gaping great white shark, its jaws rimmed with jagged menacing teeth, breaking the ocean’s surface in a terrifying predatory lunge. “Super Shark” the cover proclaimed. It was the heat of summer, and Universal Pictures had just released the blockbuster film Jaws, touted by the magazine as “a movie whose every shock is a devastating surprise”. That summer, I was one of millions of movie-goers who was happily entertained by the blood-thirsty attacks of a rogue 7.6-metre (25-ft) great white shark. No one who has ever seen that film plunges into the ocean again without at least a brief moment of nervousness, no matter how irrational it might be. Twelve years ago I jumped into the waters surrounding the tiny remote volcanic island of Isla Guadalupe, 240 kilometers (150 mi.) off the west coast of Mexico’s Baja California to experience a face to face encounter with these legendary man-eaters.

The coast of Mexico’s Isla Guadalupe at sunrise.

The great white shark is the largest predatory shark in the world with females growing up to 6.1 meters (20 ft.) in length and weighing over 2,200 kilograms (4,850 lb.). This legendary predator ranges throughout the temperate oceans of the world where it preys upon tuna, small sharks, seals, sea lions, dolphins, porpoises, seabirds, sea turtles and small whales. White sharks come to the waters surrounding Isla Guadalupe to hunt the large population of northern elephant seals that haul out on its shores.

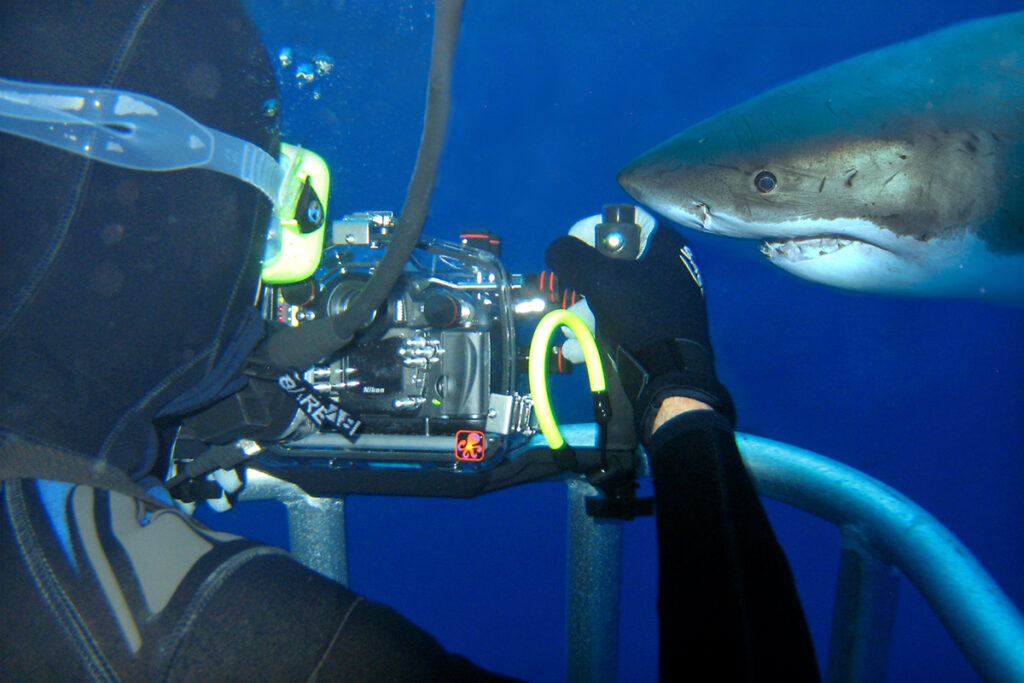

The waters surrounding Isla Guadalupe are gin clear affording visibility up to 75 metres. Three times each day, I and two other divers were lowered in a protective aluminum cage to a depth of 15 metres (49 ft.). It was exciting to watch a shark gradually approach from a distance until it was sometimes close enough to touch, something I was advised not to do. Great whites were induced to come close to the cage by the dive master stomping on a bag full of fish remains which sent out a scent signal, although no food reward was given to the sharks.

In August 2021, the great white shark made news in Atlantic Canada when a 21 year old woman was attacked and bitten while swimming near a tiny islet off the coast of Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The island where the attack occurred is a known haul out area for local grey seals, and an ideal hunting ground for great white sharks. In recent years, white shark sightings have increased in Atlantic Canada likely in response to the warming of ocean waters and the increase in local seal populations.

I used a Nikon D300S in an Ikelite housing with a single Ikelite DS51 Substrobe.

The sharks migrate to this remote Mexican island, some from as far away as the Hawaiian Islands, for one reason – the large, blubbery, elephant seals that breed there. A female northern elephant seal can weigh 600 kilograms, a large male 2000 kilograms, ample incentive for the sharks to patrol the island’s coastal waters. The need to come ashore makes the seals vulnerable to attacks from the sharks.

Shark attacks on humans in Canadian waters are extremely rare. The recent Nova Scotia attack was only the third one in the country’s history; the first being in Halifax in 1891, and the second in Vancouver in 1925. Globally there are roughly 70 to 80 unprovoked shark attacks per year, most of them nonfatal. The main culprits are usually bull sharks, tiger sharks, oceanic whitetips, and great whites. Before you become too worried by these statistics it helps to note that in New York City alone, there are a reported 1,500 cases every year of one human biting another. Spoiler alert. None of these human attacks ever ends up being mentioned on the nightly news, and you are certainly more likely to be bitten by a fellow citizen than you are to be attacked by a great white shark.

Female great white sharks can be up to a third larger than males, and typically weigh between 700 and 1,100 kilograms. The largest female ever reliably weighed tipped the scales at 1,905 kilograms and was 6.2 metres long.

Great whites, like many other shark species, have rows of replacement teeth behind their main row of teeth, ready to replace any that break off.

Great whites are ambush predators that attack from below having targeted their victims when they are silhouetted against the surface waters.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.