Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North was published in October 2022. It compares the five species of loons in the world, four of which spend the summer months nesting in Canada.

I had been thinking about writing a book on loons for nearly 50 years, starting in the early 1970s when I used a photo blind for the first time and positioned it near a nesting common loon. Whenever I spend hours quietly hidden inside a blind my mind invariably wanders and I wonder whether I could expand the experience and develop it into a book. Most often, however, the thought is a fleeting one, merely a game I play with myself to pass the time. Nonetheless, the idea of a loon book kept surfacing over the ensuing decades, usually when I was photographing in the Arctic and had spent some time working with these handsome waterbirds.

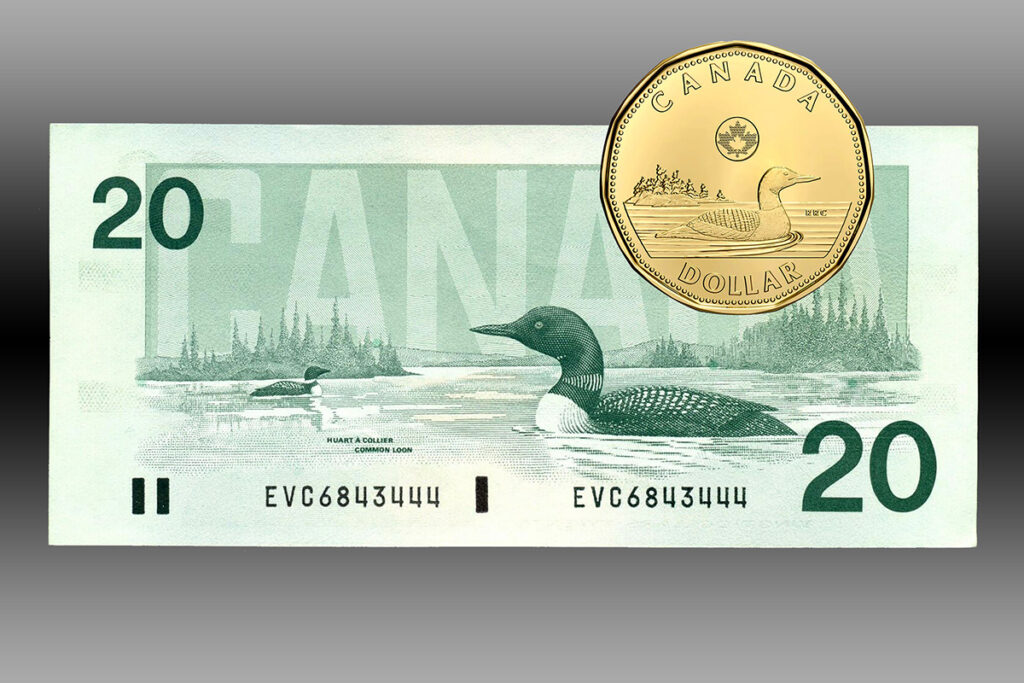

The Canadian one dollar coin featuring a common loon was first circulated in 1987, and quickly became known as the “loonie”. In 1993, a pair of common loons were featured on the country’s $20 banknote for 11 years until 2004. During those same years, Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, officially adopted the common loon as its provincial bird. It’s hard to deny that Canadians really like loons.

In March 2020, everything changed when a viral pandemic shut the Canadian borders, and all the wonderful ecotourism jobs I had lined up for the year evaporated overnight. There I was, stuck in Alberta in the midst of a global crisis, jobless, and with no plans for the months ahead.

The common loon is found throughout the forested regions of Canada from the Yukon to Newfoundland. Ninety-four percent of all the common loons in North America breed on freshwater lakes in Canada.

As Elbert Hubbard penned 100 years ago. “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade”. It was the perfect time to pour my heart into a book about loons while following the pandemic rules of social distancing and isolation.

Loons – Treasured Symbols of the North is my version of lemonade. Below is a small selection of photos from that book.

The yellow-billed loon closely resembles its close relative the common loon. The main difference between the two birds is in the colour of their bills. The yellow-bill is a threatened species with fewer than 32,000 breeding birds worldwide.

The red-throated loon, the smallest of all the loons, breeds throughout the circumpolar Arctic, up to 83° North – the highest latitude of any species of loon.

The Pacific loon, which nests throughout Arctic Canada gets its common name from its primary wintering grounds in the ice-free, temperate waters of the Pacific Ocean.

This Arctic landscape in Nunavut, with its numerous lakes varying in size and depth, is an ideal habitat for nesting yellow-billed, Pacific, and red-throated loons.

All loons lay one to two dark eggs in a nest close to the water’s edge where they can escape quickly if danger threatens.

I used a blind to photograph this Pacific loon on its tiny island nest.

On initially mounting its nest a red-throated loon gently rolls its eggs to ensure optimal incubation, something that all loon species do.

Throughout the nesting season, loons are continually challenged, sometimes three to four times each day, by outsiders intent on a hostile takeover of their territory.

When an outsider landed in this Pacific loon’s nesting territory, it adopted the so-called “vulture pose” a posture intended to communicate its agitation and readiness to fight.

This agitated Pacific loon adopted a so-called “penguin pose” to drive an intruder from its territory.

This female loon had fresh blood on her breast and belly from a fight with another female. The circled area on the edge of the nest contained a large amount of clotted blood, indicating that the injury was not a trivial one.

This common loon was still incubating an unhatched egg when the first chick hatched. When the chick got cold and needed to warm up, it would peck on its parent’s wing and move underneath.

Newly hatched loon chicks are often fed aquatic invertebrates, such as this dragonfly larva, until they get bigger and can swallow small fish.

All loon species swallow their prey whole.

This adult common loon is feeding its eight-week old chick a leech.

This defensive common loon stalked and chased an American coot and stabbed it to death when the coot accidentally swam into the loon’s territory.

Newly hatched loon chicks immediately establish a hierarchy that determines which of them gets most of the food from their parents. The chick on the right is signalling its submission.

Common loon chicks frequently ride on their parents’ backs in the first two weeks of life, in part, as a protection against underwater predators such as pike.

This chick dismounted because it wanted to swim beside its parents.

In late summer, yellow-billed loons, like other loon species, may gather on large lakes and forage together in preparation for their autumn migration.

Migrating Pacific loons, like all loons, migrate singly or in small, uncoordinated groups of a dozen or less.

When this adult loon took off from its nesting lake on September 6 I never saw it again.

Items Discussed

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.

Wayne, great photos!

We’ve just ordered your Loon book.

It’ll make a great Christmas gift for our biologist daughter-in-law (if we’re willing to give it up!).

Trust that all is well with you!

Absolutelystunning photos and info.

Many thanks for the kind words. Now if you can convince every family in Ontario to buy a copy everything will be rosy. 🤞🤞🤞