When I am initially exploring an idea for a new book, I always start by asking myself three questions. First, how many books have been written on the same subject? If there are many, it could be that the market is saturated. If there are none, or very few, I may have a fresh new idea ripe for publication, or my idea is a dud and the eventual royalties may be just enough to buy a large coffee and a box of chocolate-glazed Timbits with which to drown my sorrows.

This alligator was basking on the bank of a pond in Okeefenokee National Wildlife Refuge in southern Georgia.

Big Cypress National Preserve is a vast swamp in southwestern Florida that is home to alligators as well as black bears and endangered Florida panthers.

Second, is the project an expensive one to research and photograph, and will there be large travel costs. After 45 years in the business and more than 70 published books, I’ve only had to abandon one book idea because of the expense and difficulty of the project. The topic was Grouse of the World. When I first decided to pursue the idea in the mid-1990s I had already photographed the 10 grouse species found in North America. That left just the nine species in Eurasia. So my next step was to fly off to Sweden for an intense month of grouse hunting. Six thousand dollars ($12,000 today) and four weeks later I had managed to capture just three or four decent images to show for my efforts. If that’s all I could get in Sweden, what hurdles would I face with the grouse in Russia and China? I called it quits and the grouse book never happened.

The third question I ask myself is whether the subject is exciting and fun to photograph, and will I gain some memorable life experiences that will justify the venture even if book sales are disappointing. Question number three carries the most weight for me and explains why I spent over seven years shooting the photographs for Alligators: The Illustrated Guide to their Biology, Behavior and Conservation, which was published by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2020. In the end, the experience was every bit as thrilling as I hoped it would be.

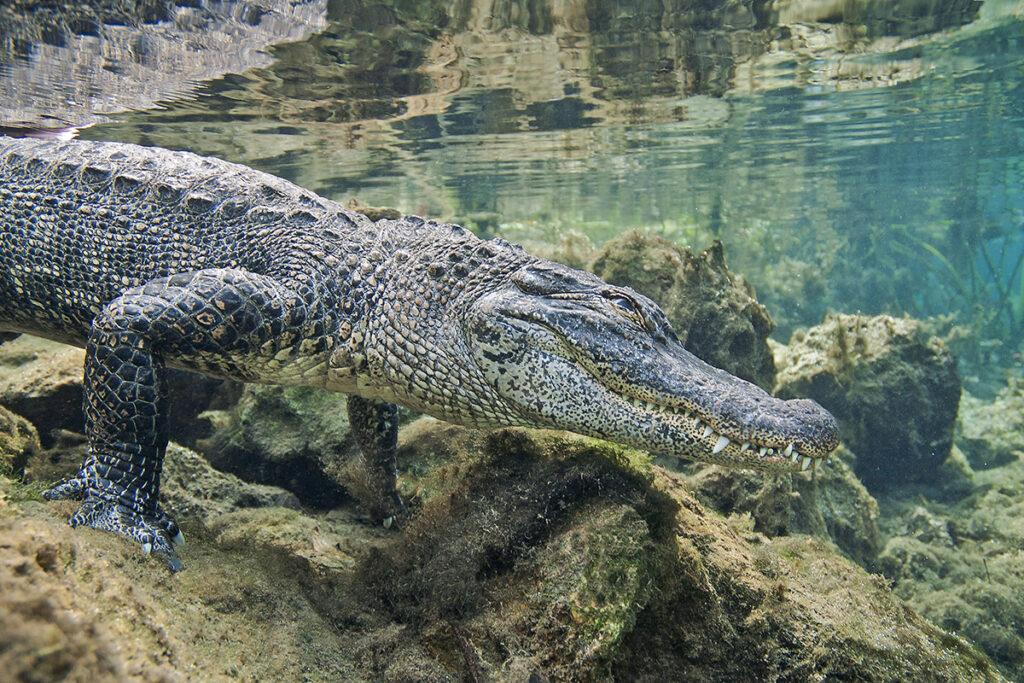

Large adult male alligator may be 4 meters (13 ft.) long and weigh over 450 kilograms (992 lbs). The largest alligator ever measured in Louisiana was 5.8 meters (19 ft.) long.

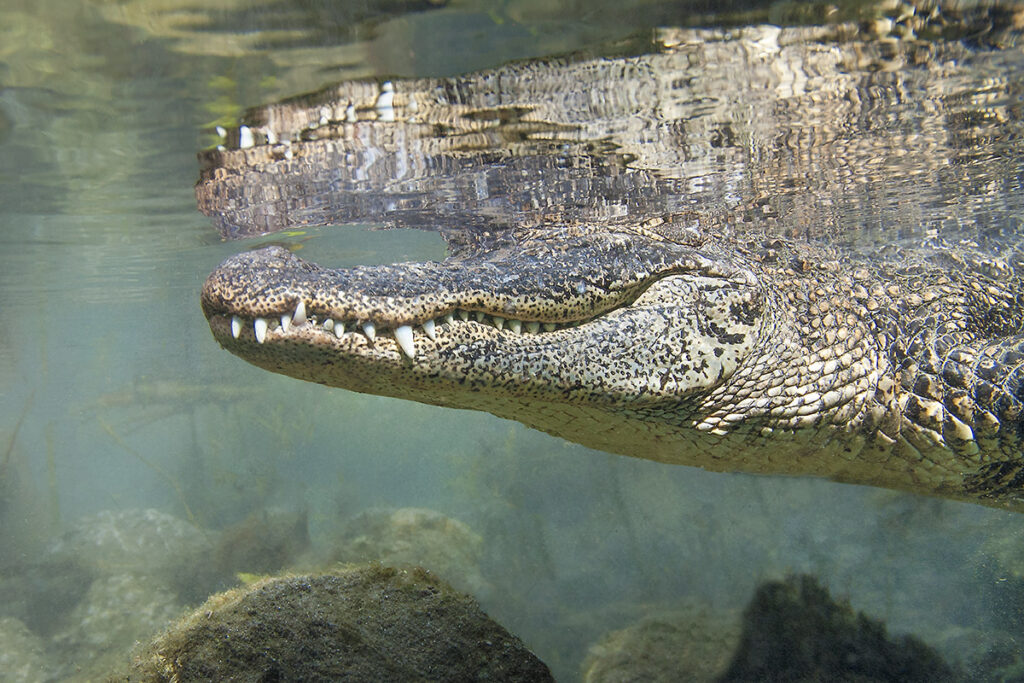

Once I had decided to do a book on alligators, I reviewed every book on alligators published in the previous 30 years to see what others had done and how I could make a new book fresh and different. I quickly discovered that most of the published alligator photos up to that time were of animals snoozing in the sunshine. There were very few photos showing action or behaviour, such as courtship, mating, predation, and hatching, few were taken at close range with wide-angle lenses, and virtually none had been photographed underwater. So there was my challenge. Photograph active behaviour, get close and intimate with my subjects, and if possible, do it underwater.

Male and female alligators may vary greatly in size. In the photograph, a small female is following a large male indicating her interest in mating.

Until 2006, I had never seriously photographed underwater even though I have been a certified scuba diver since 1973. I had frequently snorkelled with manatees in Florida and these big, curious, underwater teddy bears had sometimes approached me and tugged on my flippers. I didn’t think I wanted alligators to do the same but I really didn’t know what to expect once I got in the water with them. The solution? I talked to Dr. Kent Vliet at the University of Florida who is an expert on alligators and was my collaborator on this book project. From Kent I received a basic education in alligator etiquette. His two biggest recommendations for photographing alligators underwater were to photograph during the cold winter months when the animals are sluggish and not in hunting mode, and stay out of the water during the April/May mating season when large male alligators are aggressive and territorial. So, now that I was schooled, off I went on my new adventure and the accompanying photographs tell some of that story.

Alligators are found in nine different states in the southeastern United States, but the greatest numbers occur in Florida, Georgia and Louisiana where I did most of the photography for the book.

The camera gear I used for above-water shooting was a Nikon D700 and D850, and a selection of Nikkor lenses ranging from a wide-angle 12-24 mm zoom up to a 500 mm f/4 telephoto. For underwater photography I used a Nikon D300S in an Ikelite housing with a single Ikelite DS51 Substrobe. I’m not really skilled at using an underwater flash and occasionally in my excitement I positioned the flash too close to the camera and got backscatter when the flash illuminated particulate matter in the water.

With its eyes, ears and nostrils positioned on the top of its head, a hunting alligator can approach unsuspecting prey while keeping the bulk of its massive body hidden beneath the water’s surface.

An alligator can stay underwater for up to two hours, but an average dive usually lasts less than 20 minutes.

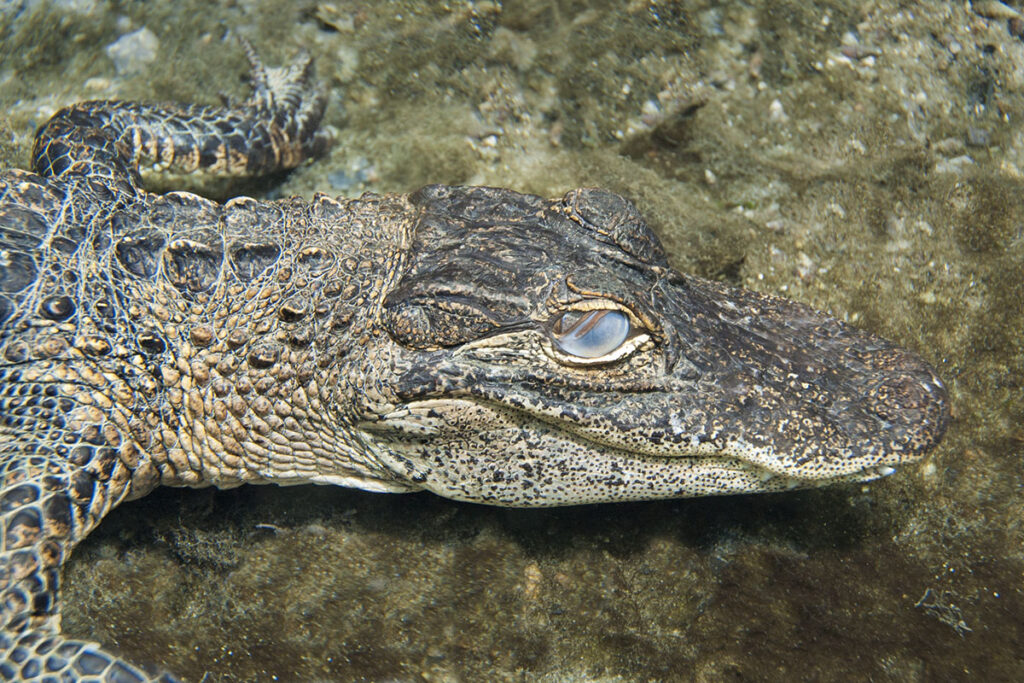

Alligators have a third eyelid, called a nictitating membrane. The milky white lid covers the eye whenever the eyes are shut or when the alligator is underwater with its eyes open. The membrane is not meant to function like a pair of swimming goggles but to protect the eyes against injury.

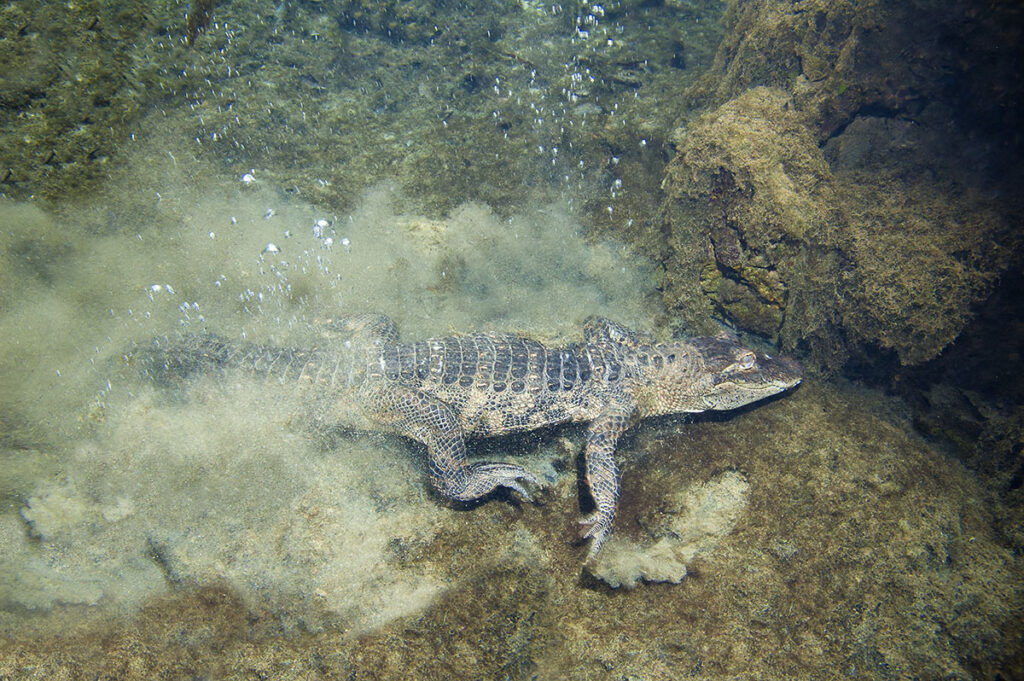

A juvenile alligator escaping to its underwater burrow. Although the entrance is underwater, the burrow chamber contains an air pocket above the level of the water.

The chirping and movement of hatchlings breaking free of their eggshells stimulates their nest mates to also emerge.

A mother alligator can be very aggressive in defense of her nest and hatchlings.

The closer a young alligator is to its mother, the safer it is from predators.

Newly hatched alligators stay together in groups called pods, and sometimes they squabble.

Once a young alligator is 1½ to 2 years old, it will finally leave the protection of its mother and move out on its own. By this age it has grown large enough to no longer be at risk from most predators.

A great blue heron has caught a young alligator.

A young alligator returns to the surface after a shallow dive.

In the 1950s, conservationists worried that the alligator might be hunted into extinction, but after decades of careful management their numbers have recovered and they are no longer in danger of disappearance.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.

Wow… beautiful… and what an adventure

I love the one of the alligator lazing on the log and of the babies on top of Mom.

Superb and very educational article.

Great Photos Wayne. How long did the photo session of your project last. Did you ever feel threatend by them? I have spent time in S Texas and have photos of an 18 footer in a preserve. Nothing like you have though!

Brilliant photography, comments and patience as usual for me. /beautiful.

Thanks to everyone for the kind words. The project took over 7 years. As I mentioned in the text, I luckily didn’t have any problem with alligators because I followed the advice of an alligator expert who said “ Don’t swim with them during the April/May breeding season, and only swim with them in winter when the water is cool and the alligators are sluggish and not hunting”.

Wayne

Nice Work Wayne

Not many people can make a slithering, scaly, ancient reptile look charming and beautiful.

Hi Tony. Many thanks for the kind words. Such praise from a fellow photographer and columnist is well appreciated.

Wayne