I became enchanted by the prairie grasslands more than 40 years ago and have been bewitched by birds even longer. Originally, native prairie grasslands occupied the entire central core of North America, roughly 138 million hectares. (340 million ac.)

From March to May, male sage-grouse cluster on traditional dancing grounds, called leks, to display and court females. Each male defends a small territory, sometimes less than 15 metres (50 ft.) across. The handsome suitor spreads his tail, struts, and inflates a large pendulous throat pouch. In the last moments of the display, the air trapped inside the pouch is suddenly released, producing two large pops—the grouse version of a satisfied burp.

This vast expanse of grass and sky stretched for over 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi.) from the aspen parklands of western Canada south to Texas, and from the jagged summits of the Rocky Mountains to the eastern hardwood forests. Today, more than 80 percent of the continent’s grasslands are no more than a memory, and native prairie continues to disappear at a rate of 40,000 hectares (100,000 ac.) a year – victims of urban sprawl and humanity’s insatiable appetite for cropland. It is no surprise that grassland birds are declining more rapidly than any other avian community in North America.

Most of the Great Sand Hills in southwestern Saskatchewan are covered with shrubs and grasses and active dunes cover less than 3% of the area, yet it’s the dunes that are the biggest draw for most visitors. Here, the wind labours over the sand, brushing the slopes with waves of ripples and drawing the crests into comforting curves.

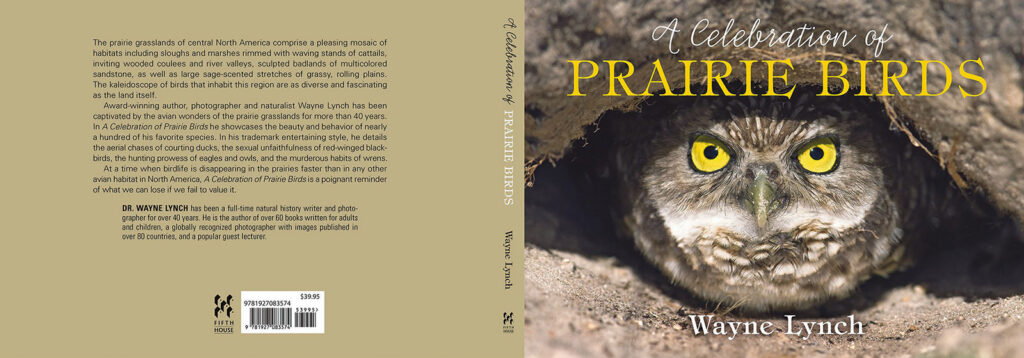

The best way to preserve these last remnants of prairie grasslands and their wildlife is to understand what we will lose if we do nothing to protect them. Grassland birds live complex and intriguing lives. In 2021, I published my 68th book, A Celebration of Prairie Birds, in which I describe some of the many fascinating details that make these creatures so interesting and satisfying to watch.

My book, A Celebration of Prairie Birds, was published in 2021 and showcases the beauty and biology of its avian inhabitants.

The habitat that most people associate with the prairies is the rolling grassy plains. Yet the prairie grasslands is a wonderful and surprising mosaic of many habitats. It includes wetlands, such as sloughs and marshes rimmed with waving stands of cattails, as well as lazy, winding rivers, and large alkaline lakes. It also contains rolling dunescapes, sculpted badlands of multi-coloured sandstone, and inviting wooded river valleys and coulees where you can retreat from the light and glare of the open sky. Together, these different wild habitats combine to make the prairie grasslands, and the birds that fill its skies, a natural sanctuary to soothe the psyche, challenge the mind, and rekindle the spirit.

Male sage grouse do not acquire full breeding plumage until they are two years old. The tail feathers of an immature male are tipped with white and more blunt than those of a mature male pictured here.

A male meadowlark will frequently move around his territory, repeatedly broadcasting his defiant song to potential rivals in every direction.

Below is a small sample of the 253 photographs featured A Celebration of Prairie Birds accompanied by some interesting biological tidbits that highlight why these birds are such fascinating creatures to observe and photograph.

The burrowing owl is a small owl, just 23 centimetres (9 in) tall, with legs nearly a third as long as the length of its body. This charming little owl is an uncommon resident of short-grass and mixed-grass prairies throughout the Great Plains. In recent decades it has suffered declines, the most drastic being those in Canada where the population may now be as low as 800 birds (500 in Saskatchewan, 300 in Alberta).

This burrowing owl chick had just taken a burying beetle (Nicrophorus sp.) from a parent. It was one of a large family of seven chicks that were huddled around the family burrow in southern Alberta.

The territorial song of the chestnut-collared longspur is often given on the wing. Having a black breast and belly makes the songster more conspicuous against the brightness of the overhead sky.

This male mountain bluebird was bringing a darkling beetle (Tenebrionidae) to his four chicks hidden in a tree cavity nest.

Among sharp-tailed grouse, the vibrancy of the male’s yellow combs and purple throat sacs are a reflection of his health and vitality – cues a female can use to evaluate him as a potential mate.

This loggerhead shrike was caching a dead deer mouse in its larder. A well-stocked larder advertises not only the quality of a male shrike’s territory but also his proficiency as a hunter and provider, and, not surprisingly, these attributes are attractive to female shrikes looking for a mate.

The ear tufts in this short-eared owl have nothing to do with hearing. Some biologists speculate that their principal purpose is to camouflage the birds by breaking up the bird’s outline and mimicking the ragged top of a broken branch. In some instances, however, the erection of the ear tufts may be a reflection of anxiety caused by a nearby predator or rival.

A photo blind is the most important piece of equipment I use to get intimate photographs of birds and other wildlife.

The male red-winged blackbird’s scarlet epaulets are important signals of dominance and ownership. When an inquisitive scientist blackened the red shoulder patches on a group of males, more than half of them immediately lost their territories to rival intruders.

When a marbled godwit first lands, it momentarily holds its wings outstretched to display the rich cinnamon colour underneath.

These male marbled godwits fought for over 11 minutes, after which the winner flew off with the female who was nearby watching the spectacle.

Only male marsh wrens sing, and these little testosterone charged songsters can really whistle. Each male marsh wren may sing over 200 different songs. Neighboring males commonly engage in vocal duels, imitating each other’s songs and trying to outdo one another, and these long-winded singers chatter day and night.

American white pelicans are hard to confuse with any other waterbirds. They are massive birds with wingspans reaching nearly 3 meters (10 ft.); some individuals may weigh as much as 13.5 kilograms (30 lb.), making them among the heaviest of flying birds.

The male horned grebe often brings a gift of nesting material prior to mating, and then ends the brief mounting with a penguin display in which he vigorously treads water and rises upright.

These handsomely feathered male white-faced ibises fought for over a minute while an unconcerned female foraged nearby.

The mating sequence of the American avocet starts with solicitation, followed by mounting, and concludes with a stylized beak display and a celebratory march.

The female black-necked stilt on the left is thrashing the water in a courtship display soliciting copulation. Notice the distinctive brownish tinge on the feathers of the female’s back; otherwise the sexes are indistinguishable.

The courtship of ruddy duck is amusing to watch. The cocky little drake could easily be mistaken for a windup toy, especially when he performs his “bubbling” sequence, the major display used by courting males. More than 40 bubbling displays may be performed by a single male in just 20 minutes. It seems the vigor and frequency of the bubbling display reflects the dominance of the male. Conclusion: top drakes really bubble.

The black tern is an agile flier that will skim the water surface in the manner of a swallow, doggedly pursue a dragonfly on a zigzag chase, will vigorous engage a rival in an energetic dogfight.

This Franklin’s gull is hoping to add a large cattail leaf to its nearby floating nest.

The sandhill crane formerly nested in the prairies. It now stops only to roost and feed in the area as it passes through on its annual spring and autumn migrations in April and September. The birds commonly roost in shallow open wetlands and feed in nearby stubble fields.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.

I am an absolute awe of your photos. Each and every one of the images displayed in this article had me ooing and swing with great pleasure. Thank you so much for sharing these images. I always look forward to your work in the photo news magazine 😊

Hi Colleen. Thanks for the kind words. I would have answered sooner but I was working in Arctic Norway leading a photo group searching for polar bears. We found 53 bears in the seasonal pack ice. It was an exciting adventure and a great photo shoot.

Dr Lynch’s photography and knowledge of nature is excellent and he imparts that knowledge well. I truly enjoy his work.

Hi Marlyn. Thanks for the kind words. I have always felt that knowing one’s wildlife subject always leads to better photos and a richer experience.