I have been addicted to nature trivia since I was a boy. I always wanted to know which animal has the strongest claws, the lightest bones, the most enormous mouth, the longest lifespan, and the biggest belly. Today, many decades later, whenever I need a trivia fix, I can always count on a book written by my late friend Frank Todd: 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Although I have owned the book for many years, I still have not managed to make it through to the end because every new piece of trivia seems to send me searching for another book. This delightful quest continues to this day, and I’m hopeful this month’s photos will ignite your own nature trivia addiction.

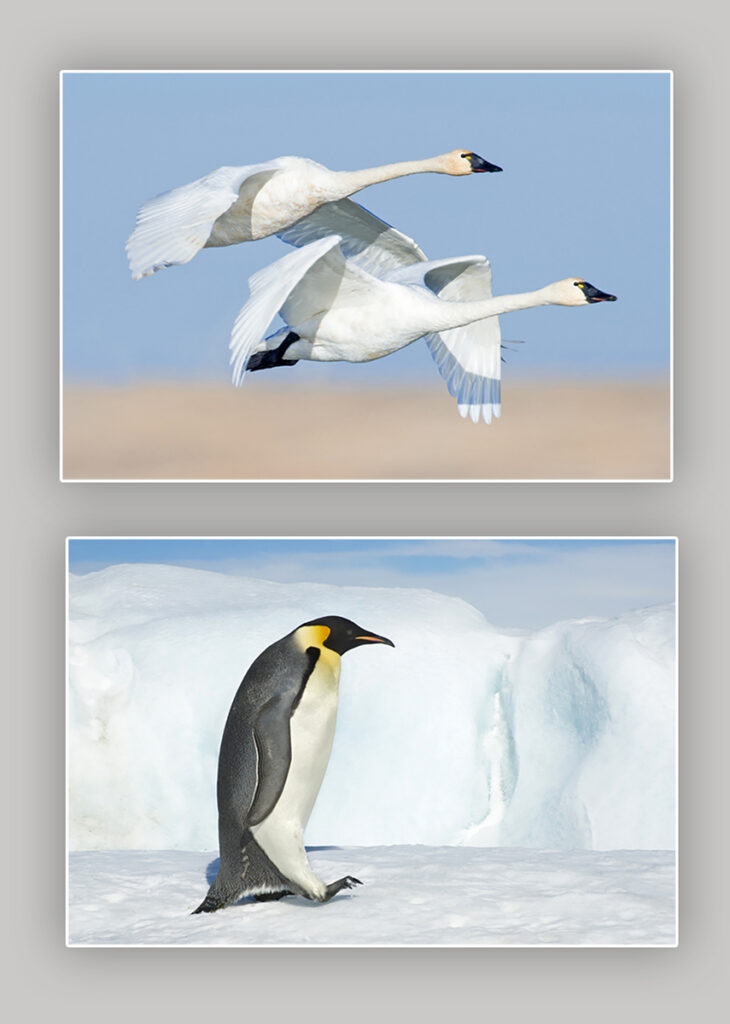

Most Feathers: In the 1940s, a team of very patient biologists counted 25, 216 feathers on an adult tundra swan. They discovered that 80% of the feathers were tiny ones located on the bird’s head and neck. That record held for over 80 years until a tenacious team tackled an emperor penguin and counted an astonishing 80,000 feathers on a single bird.

Greatest Wingspan: The wandering albatross, with a wingspan up to 3.65 m (12 ft), thrives in the windswept latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere, the so-called roaring 40s and furious 50s. The extinct giant teratorn, which was an enormous vulture-like bird that lived in South America 7 to 9 million years ago, had an even greater wingspan, measuring up to 7.6 m (25 ft), making it about the size of a small glider.

Heaviest Flyer: This male kori bustard in East Africa is courting a female. Although it spends three-quarters of its time on foot feeding on grasshoppers, dung beetles, and scorpions, the kori bustard’s 19-kilogram (40-lb) body weight makes it one of the heaviest flying birds in the world.

Fastest Flyer: In a feather-rippling power dive, called a stoop, an attacking peregrine falcon tucks its tapered wings and falls like a thunderbolt from the floor of the sky. In such a dive, the peregrine is the fastest bird on wings, reaching a recorded speed of 390 km/hr (242 mph). The victim is killed with a smashing blow from the peregrine’s semi-clenched feet or is slashed to death with its trailing rear talons.

Highest Flyer: In 1973, a Ruppell’s griffon vulture collided with a commercial jet at an altitude of 11,277 m (37,000 ft) over the Ivory Coast in West Africa. The plane lost one of its engines in the impact but landed safely soon afterwards.

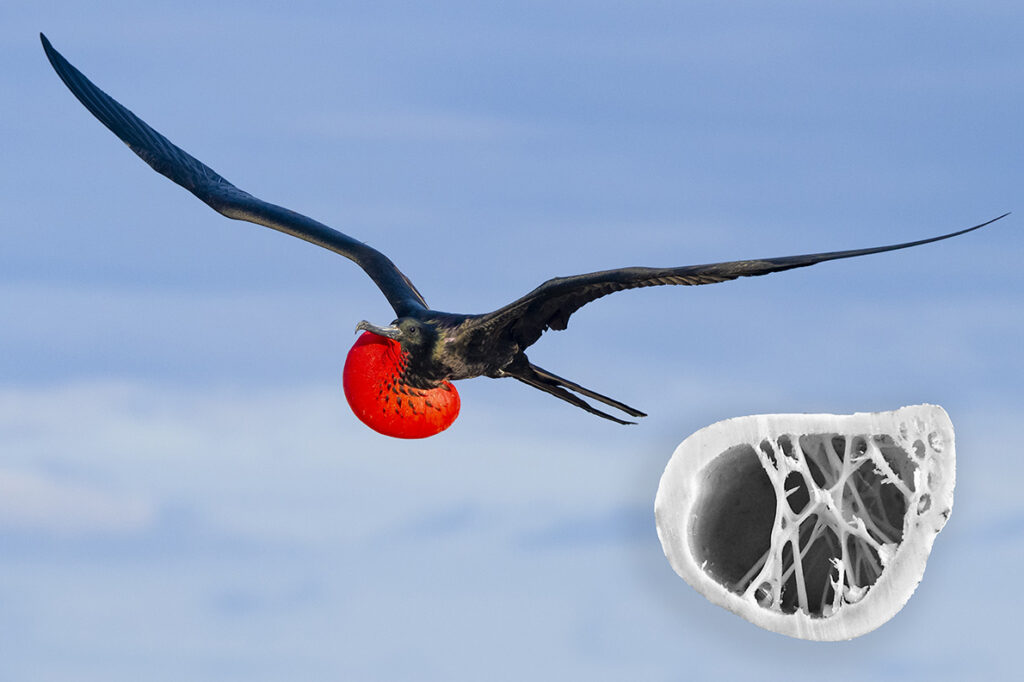

Lightest Bones: The magnificent frigatebird of the American tropics has the lightest skeleton of any bird – accounting for just 5% of its total body weight, which is less than the weight of its feathers. The bird’s largest bones are filled with air spaces to lessen their weight and reinforced with internal struts to maintain their strength.

Most Dangerous Feet: The double-wattled cassowary lives in the tropical rain forests of northern Australia. Females can grow up to 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) tall and weigh up to 58 kg (128 lbs). Males are 50% smaller than their partners.

The double-wattled cassowary is one of the most dangerous birds in the world. Its three-toed feet are thick, powerful, and equipped with lethal dagger-like claws up to 12 cm (4.7 in) long on its inner toes. In defending themselves or their young, they can jump high and kick powerfully, inflicting serious injury.

Longest Toes: The long toes of the wattled jacana of South America are designed to disperse the bird’s weight, enabling it to walk easily on floating vegetation, which explains their alternate name, the “lily-trotter”. The toes on chicks reach adult size even before the young birds can fly.

Largest Eyes: The ostrich has the largest eyes of any bird, measuring up to 5 cm (2 in) in diameter. In fact, the ostrich has the largest eyes of any land vertebrate. The human eyeball is just 2.2 x 2.7 cm (0.9-1.1 in) in diameter. For those readers addicted to nature trivia as much as I am, the 100,000-kilogram (100-ton) blue whale has the largest eyes of any living vertebrate, 15 cm (6 in) in diameter; and the elusive giant squid, which is the world’s largest invertebrate, 25 cm (10 in) diameter eyes.

Smelliest Bird: The hoatzin (pronounced WATT-zin) is a South American rainforest bird whose diet consists primarily of the leaves of over 50 kinds of tropical plants. The hoatzin digests its meals in an enlarged crop, relying on microbes to break down the plant material. Because of the hoatzin’s unique leafy diet and how it digests its food, it smells like stinky cow manure.

Longest Penis: Most birds don’t have a penis. The exceptions include the ratites (ostrich, emu, rhea), flamingos, and waterfowl, all of which have a swelling on one side of their cloaca which functions like a penis and allows sperm to be deposited internally. The 46-cm (18-in) long lake duck of South America holds the record for the longest penis relative to its body size. One male lake duck had a 42.5-cm (16.7-in) long penis. The duck’s penis is covered with dense spines and shaped like a corkscrew. The bird’s lengthy, elaborate reproductive equipment is likely a strategy to prevent sperm displacement by rival males in this promiscuous waterfowl species.

Strongest Gizzard: The gizzard is the muscular, grinding part of a bird’s stomach that performs the same function as teeth do in mammals. Often, a bird’s gizzard may contain small stones to help in the grinding process. The wild turkey is reputed to have the strongest gizzard of any bird. In one study, a turkey crushed 24 unshelled walnuts in under four hours and supposedly turned surgical scalpel blades into grit in less than 16 hours.

Best Submarine: The anhinga can control its buoyancy so well that its head and neck gradually sink like the periscope on a submerging submarine. The anhinga has solid bones, and feathers that get soaked through to its skin. These features make the bird almost neutrally buoyant, so it controls its sinking rate by gradually expelling the air in its lungs and air sacs.

Best Hitchhiker: This is a photograph of a yellow-billed oxpecker in its natural habitat – on the back of a mammal, in this case, a giraffe. Oxpeckers, of which there are two African species, specialize in feeding on blood-engorged ticks, which they find by scissoring through the fur of their hosts. They also feed on flies, botfly larvae, ear wax, and the dried blood encrusting recent wounds. Yum, yum.

Cleverest Hunter: You might think this African black heron is just camera-shy. Actually, it is using a unique foraging strategy called “canopy feeding”. The heron uses its wings like an umbrella to cast a shadow over the water. The shade reduces glare and makes fish and aquatic invertebrates easier to see and capture.

Best Pirate: In the world of birds, piracy is an uncommon way to make a living, but the three species of Arctic jaegers – the parasitic jaeger (pictured here), pomarine jaeger, and long-tailed jaeger – are all experts at it. Jaegers (pronounced YAY-gers) are close relatives of the gulls and they’ve modified the basic gull pattern so that in many ways, they resemble birds of prey. They have strongly hooked bills, sharp curved claws, and hard, tough scales on their legs. Female jaegers are also larger than males another characteristic they share with birds of prey.

The most common victims of jaegers are seabirds, especially terns, kittiwakes, and puffins. Typically, a jaeger swoops down from above or makes a head-on attack that forces the bird to slow down. The jaeger may pull food right out of a seabird’s mouth. More often, the robber harasses the victim by chasing it and tugging at its wingtips or tail. In those attacks, the desperate seabird typically regurgitates its catch, which is what the kittiwake in this photo is doing, and the jaeger catches the stolen food in mid-air or retrieves it from the surface of the water.

Dullest Diet: For at least six months of the year, the spruce grouse, a year-round inhabitant of the boreal forests of North America, eats nothing but the high-fibre, low-nutrient needles of spruce and jack pine trees. It compensates for its dull, low-quality diet by eating lots of needles, fully stuffing its crop at the end of each day and slowly digesting the contents during the night.

Deepest Diver: Among birds, penguins are the undisputed master divers. King penguins have been recorded diving to depths of 325 meters (1,060 ft.), and big-bodied emperors (pictured here) can plunge to 564 meters (1,850 ft.) and stay submerged for nearly 28 minutes.

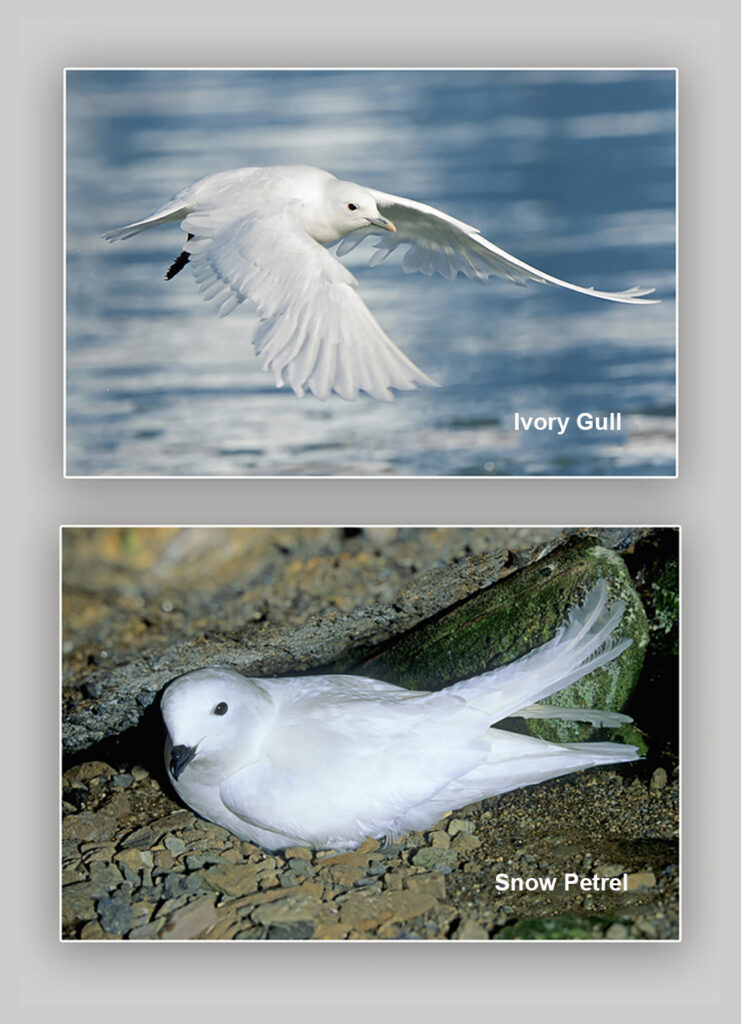

Most Polar: Two pure white, unrelated birds occupy the most extreme polar latitudes on Earth. In the Arctic, the ivory gull is commonly found above 70°N and has been reported as far north as 88°N, just 223 km (139 mi) from the North Pole. In the south, the polar specialist is the snow petrel, a close relative of the albatross. The handsome petrel breeds exclusively in Antarctica and ranges as far south as 73°S and as far inland as 440 km (273 mi), necessitating a lengthy commute to the ocean to feed.

Best Spelunker: The nocturnal oilbird of South America is one of the few avian species that is known to echolocate – an ability that is common among bats. The tropical oilbird forages at night for fruit, returning before sunrise to roost and nest deep within caves where it uses its echolocation to navigate in the total darkness.

Best Weaver: This lesser masked weaver belongs to an African family of elaborate nest builders. The weaverbirds build their nests at the tips of overhanging branches so tree-climbing snakes and other predators cannot approach unnoticed. The male birds use their bills to stitch and intertwine grasses into a tight, waterproof, protective, globular nest intended to satisfy the discerning eye of potential female partners. A male may need to weave half a dozen nests before one of them finally impresses a female.

Most Nests: The male marsh wren of North America builds more nests than any other bird. All are intended to lure a prospective female mate. Male marsh wrens with a single female partner may build up to 22 nests, and a bigamous male may eventually build 25 nests. The nests rejected by the female serve as dummy nests that help confuse potential predators.

Warmest Nest: The common eider, weighing up to 2.6 kilograms (5¾ lbs), is the largest duck in the Arctic and the source of the famous eiderdown, the warm filling used in sleeping bags, quilts, and winter jackets. The female eider plucks the soft, fluffy feathers from her belly to line her nest. It takes about 60 nests to produce 1 kilogram (2.2 lbs) of eiderdown, which currently sells in Canada for a whopping $3,571.00.

Most Precarious Nest Site: The fairy terns of Midway Island in the tropical North Pacific, like fairy terns everywhere, build no nest but simply balance their single egg on a branch, sometimes 20 m (66 ft) above the ground. The precarious location is intended to protect the egg from ground predators, although it is highly vulnerable to windstorms.

Hottest Nest Location: The gray gull, which nests in the Atacama Desert of South America, must endure ground temperatures up to 50°C (122°F) – hot enough to fry an egg.

Fiercest Nest Defense: The great horned owl has been called “the tiger of the skies” for good reason. In defense of its eggs or young, the bird may attack with incredible savagery. There are scores of well-authenticated cases on record where humans have been blinded and suffered severe injuries to their head, throat, chest, back, and groin by enraged attacking great horned owls. The attacks are bold, slashing, and very dangerous, made even more so by the total unexpectedness with which they strike. A nature photographer in Saskatchewan learned this lesson the hard way when an angry great horned owl knocked him out of a tree. In the fall, he fractured his pelvis and had to drag himself to the road to be rescued.

I am frequently asked whether I’ve ever been attacked by wildlife. Surprisingly, it’s only happened to me twice in 46 years. The first time I was hiking on Prince of Wales Island, Nunavut, when I accidentally approached an unseen nesting snowy owl. Her male mate swooped on me from behind and struck me on the back of the head with his clenched feet. I was wearing a heavy wool hat so I wasn’t injured, although I was startled by the attack.

In the second attack, I wasn’t so lucky. I had found a northern hawk owl nesting in the top of a broken snag in Churchill, Manitoba. Hawk owl chicks, like the one pictured here, jump from the family nest and hide separately on the ground many weeks before they can fly while their parents continue to feed them.

On the day of the attack, the three chicks had left the nest, but I couldn’t see any of them hiding on the ground. I loitered to take a photo of the adult female, who was calling excitedly from the top of a nearby snag. While I was busy fiddling with my camera gear, I was suddenly hit in the back of the head by the male. The blow was so hard it felt as if someone had punched me. The male had hit me with his toes clenched, so I wasn’t cut, although the bump later swelled into a sizeable “goose egg”. When I stubbornly continued to focus on the calling female, the male struck me again, but this time, he hit me in the forehead with his talons exposed just above my right eye. Blood immediately began to drip into my eye, and for a moment, I couldn’t see well. I wondered whether he had punctured my eyeball. The second attack scared me, and I ran away as fast as I could. By the time I got back to my vehicle, the bleeding had stopped, and I saw the three puncture wounds just above my eye where the talons had hit me. Lesson learned.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.

Thank you! This is super appealing to me. I really enjoy the information that is given about the different birds! Really great and interesting!

Thanks Richard. Sorry for the delay in responding but I was in South America until today.

Fabulous article and great pics. I learned a lot abour feathered friends, some of which I had never heard of. Good job!

Hi Wally. If you love avian trivia you should try to find a copy of the book I mention at the beginning of my column. I keep a copy in my car so whenever I have to kill some time I have a fun way to keep myself entertained.

Wayne