I decided to continue the theme I began last month with “Extreme Birds” and feature extreme examples of reptiles this month.

Worldwide, there are roughly 10,000 reptile species, including caiman, alligators, crocodiles, turtles, tortoises, snakes, lizards, and a single species of tuatara. Below are some of my favourite extreme reptiles.

Longest Lifespan: Originally, there were giant tortoises in southern Asia as well as in North and South America, but they all disappeared, many a consequence of overhunting by humans. Today, these large chelonians only occur naturally on Aldabra Island in the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean, and in the Pacific equatorial islands of the Galapagos. The giant tortoise commonly lives for 100 years or more, but there are verified records of a few living as long as 150 years.

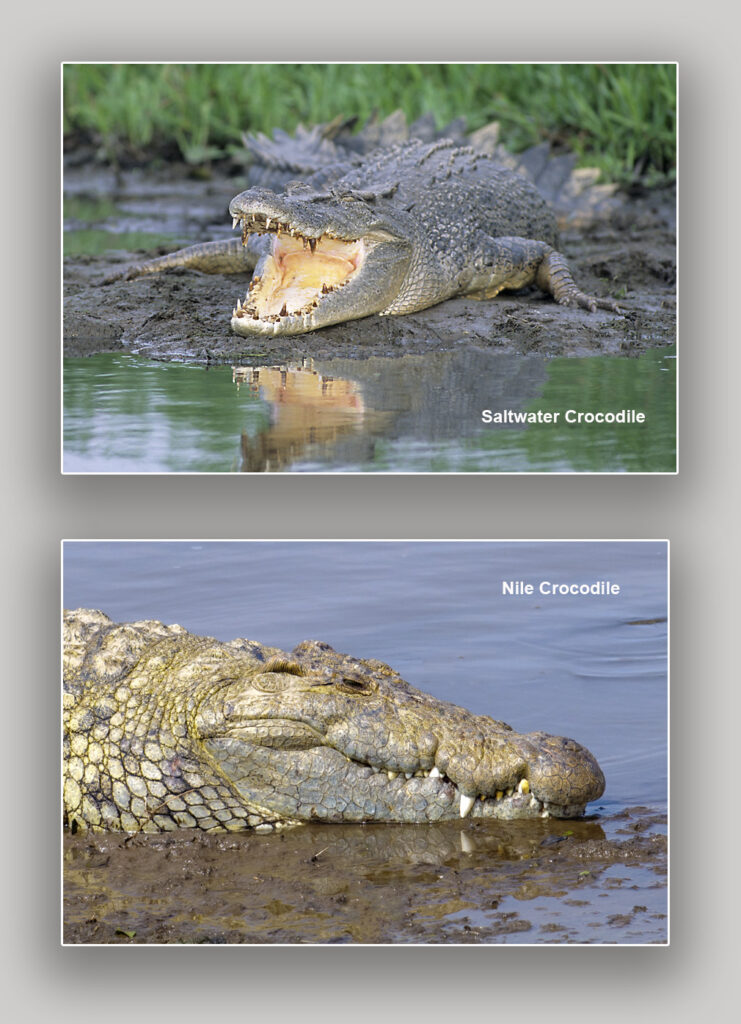

Greatest Hunger for Humans: Two species of large crocodilians, the saltwater crocodile of Australia and Southeast Asia and the Nile crocodile of sub-Saharan Africa, routinely attack and sometimes eat humans. Researchers estimate that more than 1,000 people are killed every year by these two dangerous species of crocodile, both of which can weigh more than 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lbs).

Venomous Lizards: Worldwide, there are more than 7,000 species of lizards, but only five are venomous: the Gila (pronounced HEE-la) monster of the American Southwest and the four species of beaded lizards in Mexico and Guatemala. None of these dangerous lizards have fangs with which to inject their venom as do venomous snakes. They simply bite and repeatedly chew on their victim, letting the venom seep into the wound. The sluggish Gila monster typically feeds on invertebrates, ground-nesting birds, and their eggs. Its venom is used primarily as a defensive weapon, and although the venom usually produces nothing more than severe pain, it also contains a powerful neurotoxin strong enough to sometimes kill a human.

Most Specialized Diet: The 20-centimetre-long thorny devil of Australia eats only ants, and only those in the genus Iridomyrmex, consuming thousands in a single day.

Most Unusual Defense: Although the Texas horned lizard trusts in its cryptic coloration to hide it from sharp-eyed roadrunners and hawks, as well as its spiny armour to discourage hungry snakes, it relies on its strangest defense to protect itself if it’s grabbed by a predatory desert fox or coyote. It shoots a narrow stream of blood out the corner of its eyes. Researcher Wade Sherbrooke, whom I met in Arizona in 2006, wrote in his fascinating book The Horned Lizards of North America “Beforehand, the eyelids [of an irritated lizard] become swollen and engorged with blood. Suddenly, a fine stream of blood, the thickness of a horsehair, shoots out from the parted edges of the closed eyelids. The stream can come from one or both eyes and can spray a distance of 6 feet. Each discharge lasts a second and may be repeated numerous times. A considerable amount of blood may be lost by the lizard, but it quickly recovers from the experience without obvious ill effects”.

Deepest Diver: The leatherback sea turtle is the largest turtle in the world, weighing up to 900 kilograms (1,984 lbs). It is the world’s most northerly ranging sea turtle foraging in the cold ocean waters off the coasts of Labrador and southern Greenland and in the Barents Sea. It hunts jellyfish at depths down to 1,230 metres (4,035 ft.). These photos were taken in Trinidad where many Canadian leatherbacks travel to mate and lay their eggs.

World’s Tiniest Lizard: Madagascar, known for its great diversity of endemic chameleons, is home to the stump-tailed chameleon, the smallest lizard in the world.

Most Tantalizing Tongue: The 100-kilogram (220-lb) alligator snapping turtle lives in the fresh waters of the southeastern United States. It is an ambush predator that sits underwater with its mouth open while it wiggles its pink, fleshy, worm-shaped tongue, hoping to lure a curious fish within striking distance.

Nosiest Reptile: During the spring breeding season, male American alligators bellow and slap their heads on the water’s surface to communicate with rival males. Females also bellow but at a higher frequency than males, perhaps a reflection of the smaller size of their chest cavity. Bellowing is contagious, and when one alligator bellows, its neighbours may join in the chorus. Following a bellow, the water above an alligator’s back erupts in a “water dance” caused by subsonic vibrations coming from its chest.

Heaviest Snake: The green anaconda of South America is the heaviest of all snakes, with a verified maximum weight of 97.5 kilograms (215 lbs). Historically, there’s a claim of an anaconda shot in Guyana in 1937 that was 5.9 metres (19 ft.) long and weighed 163 kilograms (359 lbs), but that report has never been substantiated. Although the green anaconda is the heaviest snake on record, the reticulated python of Southeast Asia is the longest with a record length of 6.95 metres (22 ft.10 in). The anaconda in this photograph had just eaten a capybara, the world’s largest rodent, and it was digesting its bulky meal at the mouth of a burrow in central Brazil.

Most Destructive Reptile Invader: The bulky Burmese python, a native of Southeast Asia, was first sighted in Florida’s Everglades National Park in the 1990s, likely escapees from reptile breeders or pets that were purposefully released when they grew too large to manage. Since then, their numbers have exploded, and their predatory behaviour has impacted the local ecosystem disastrously. Many native mammals have declined as a result, including bobcats, Virginia opossums, raccoons, white-tailed deer, and marsh rabbits.

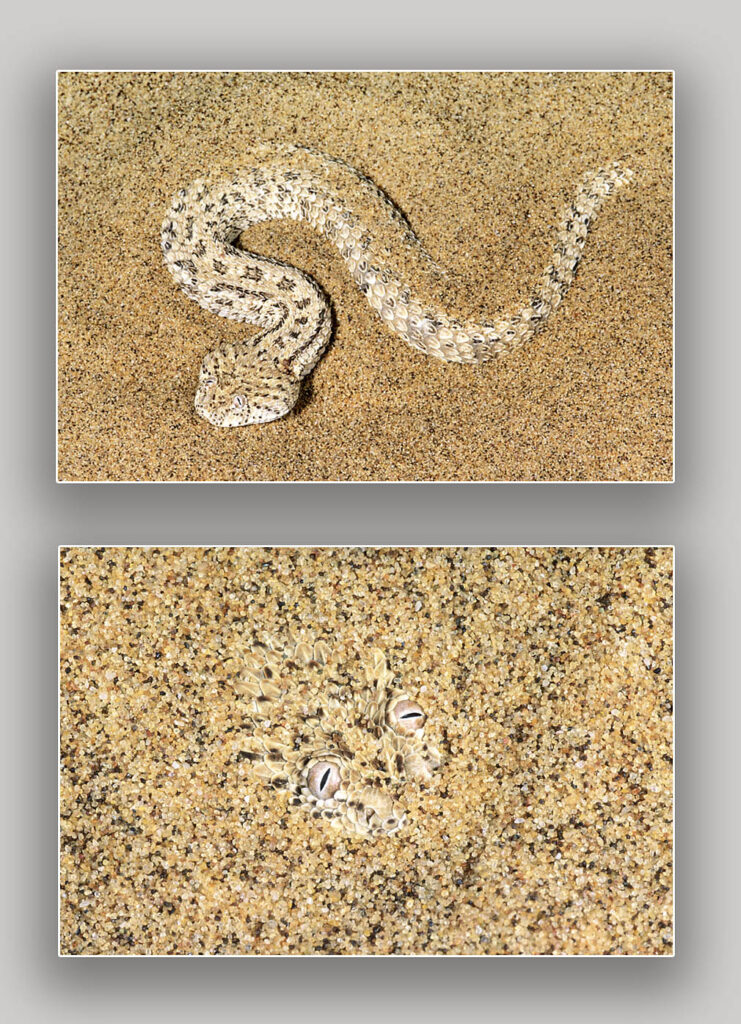

Most Unusual Eyes: The Peringuey’s adder is a desert-dwelling snake native to Namibia in southwestern Africa. The eyes of this small, venomous viper are located on the top of its head. It is an ambush predator that shuffles itself into the sand until only its eyes are above the surface, after which it waits for an unsuspecting barking gecko or sand lizard to stray near enough to be envenomated and eaten.

Trickiest Tail: The snake in this photograph is a juvenile copperhead, a venomous pit viper endemic to the eastern United States. Its bright yellow tail is an example of a “caudal lure”. Typically, the young snake relies on its cryptic body coloration to camouflage it in the leaf litter on the forest floor while it wags its conspicuous colourful tail to lure a curious victim within striking distance.

My Most Memorable Snake: I was 10 years old when I first saw a photograph of an emerald tree boa, a spectacularly beautiful snake that lives in the steamy lowland rainforests of South America. To me, this spectacularly handsome snake embodied all the mystery, magic, and danger of the rainforest – a worthy quest for an adventure–hungry boy. Fast forward nearly 60 years to the rainforests of Guyana, when a tip from a local hunter had me racing in a small boat through the treacherous rapids of the Essequibo River to a tiny native village with the hope of realizing a childhood dream. The two-metre (6.5-foot) long wild boa was looped on a branch along a jungle trail at eye level, just as I had hoped it would be. I was energized for days afterward.

Best Mimic: Henry Walter Bates was a famous British naturalist-explorer who lived in the 1800s and collected specimens in the Amazon rainforests of South America. He proposed a hypothesis in which harmless species sometimes evolved an effective anti-predator strategy by resembling dangerous species, thus gaining protection from the mimicry. His hypothesis is known today as Batesian mimicry. The harmless scarlet kingsnake and the venomous coral snake are textbook examples of Batesian mimicry. The simplest way to differentiate between the two species is to remember the rhyme “Red touching black, friend of Jack. Red touching yellow, kill a fellow”.

Most Gregarious Lizard: The marine iguana of the Galapagos Islands lives in coastal colonies, sometimes numbering in the hundreds. Unlike many species of colonial seabirds, sea lions, and seals, marine iguanas interact very little with each other, despite often touching each other when they are basking along the shore.

Only Marine Lizard: Today, less than 1% of the world’s 10,000 reptiles live in the oceans. These include the 7 species of sea turtles, the roughly 60 species of venomous sea snakes, the man-eating saltwater crocodile, and one species of lizard, the marine iguana of the Enchanted Islands of the Galapagos.

The marine iguana eats only algae that it scrapes from the rocks. Through natural selection, it has evolved a number of adaptations to exploit its ocean environment. The marine iguana has long claws to grip wave-battered, slippery rocks, a flattened tail for sculling through the surf, and a blunt snout that lets it get close to the algae that it grazes upon.

Large iguanas dive to depths of up to 5 metres, and they can stay underwater for up to 45 minutes. Typically, when an iguana heads out on a dive, its body temperature is at an ideal 37°C (98°F). During a dive, the cold water quickly saps heat from its body, dropping its core temperature to 25°C (77°F). Bigger-bodied iguanas lose body heat slower than smaller iguanas, and for this reason, only the largest males feed offshore. Females and smaller males feed on algae exposed in the intertidal zone.

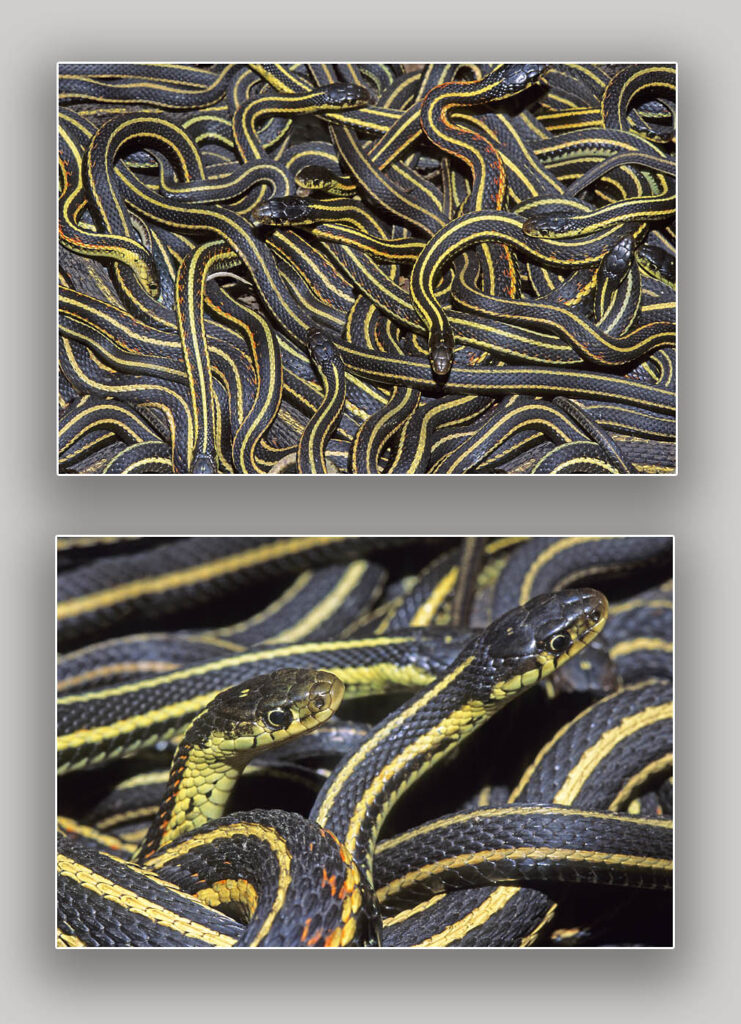

Greatest Reptile Aggregation: Arguably the greatest regular aggregation of reptiles in the world is the annual concentration of overwintering red-sided garter snakes in the Interlake Region of southern Manitoba. As many as 10,000 garter snakes may share the same winter den. Throughout the winter, the snakes clump together in the darkened depths of the den where temperatures hover around the freezing point. The warmth of spring lures them to the surface. Hundreds, and even thousands, may surface at once. The ratio of males to females around the den entrance may be as high as 50 to 1. As each female appears at the surface, she is mobbed by male suitors. “Mating balls” are formed, consisting of a single female intertwined with as many as 100 males, each intent on copulation. The female is cold and torpid when she first emerges, and her sluggishness probably works to the advantage of the courting males. An odour chemical, called a pheromone, detectable in the skin of the female’s back, advertises her sex and her readiness for mating.

Strangest Locomotion: Sidewinding is a unique form of locomotion used by snakes to traverse sandy and muddy terrains. The movement produces a distinctive track pattern. The photograph is of a sidewinder rattlesnake which I took in the Imperial Dunes in southeastern California.

Best Butt Breather: The painted turtle ranges the farthest north of the eight turtle species found in Canada. Painted turtles, like most adult turtles, cannot survive freezing temperatures, so in winter, they must retreat to some location where the temperature stays above 0°C. The most popular site is in the deep water on the bottoms of lakes and ponds. Here, the turtles get chilled to the same temperature as the water, but even though their metabolism slows down greatly, they still require a minimum amount of oxygen to survive. Turtles, like humans, have lungs and normally breathe air. In winter, a painted turtle may be trapped underwater for several months when lakes and ponds freeze over, preventing them from reaching the surface and breathing normally. They solve this problem by absorbing most of the oxygen they need through a rich network of blood vessels around their cloaca, which is the chamber under their tail at the rear end of their body. To survive, turtles become butt-breathers.

Most Protective Mother: A mother alligator can be very aggressive in defense of her nest and hatchlings. The closer a young alligator is to its mother, the safer it is from predators.

Gaudiest Reptile: The rainbow agama lizard of sub-Saharan Africa must surely be one of the world’s most colourful reptile species. Naturally, the colour is most intense in territorial males during the mating season.

Strangest Reptile Nose: The tree-climbing spear-nosed snake of Madagascar can be up to a metre long. Only males have an elongated nose, the function of which is unknown. The snake is an ambush predator that feeds on lizards and frogs. If handled gently, as I did with this individual, it remains calm and reluctant to bite. Nonetheless, it is mildly venomous, and a bite can cause severe pain in humans.

Best Natural Solar Panel: I photographed this Namaqua chameleon in the Namib Desert of southwestern Africa, where overnight fog can cool the desert dramatically. I found the chameleon shortly after sunrise. It was sluggish and dark coloured. As the sun burned off the fog, the air temperature rose, and the chameleon slowly turned white. By basking broadside in the sunshine, the chameleon was able to raise its body temperature enough to become active once again.

About the Author – Dr. Wayne Lynch

For more than 40 years, Dr. Wayne Lynch has been writing about and photographing the wildlands of the world from the stark beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic to the lush rainforests of the tropics. Today, he is one of Canada’s best-known and most widely published nature writers and wildlife photographers. His photo credits include hundreds of magazine covers, thousands of calendar shots, and tens of thousands of images published in over 80 countries. He is also the author/photographer of more than 45 books for children as well as over 20 highly acclaimed natural history books for adults including Windswept: A Passionate View of the Prairie Grasslands; Penguins of the World; Bears: Monarchs of the Northern Wilderness; A is for Arctic: Natural Wonders of a Polar World; Wild Birds Across the Prairies; Planet Arctic: Life at the Top of the World; The Great Northern Kingdom: Life in the Boreal Forest; Owls of the United States and Canada: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior; Penguins: The World’s Coolest Birds; Galapagos: A Traveler’s Introduction; A Celebration of Prairie Birds; and Bears of the North: A Year Inside Their Worlds. In 2022, he released Wildlife of the Rockies for Kids, and Loons: Treasured Symbols of the North. His books have won multiple awards and have been described as “a magical combination of words and images.”

Dr. Lynch has observed and photographed wildlife in over 70 countries and is a Fellow of the internationally recognized Explorers Club, headquartered in New York City. A Fellow is someone who has actively participated in exploration or has substantially enlarged the scope of human knowledge through scientific achievements and published reports, books, and articles. In 1997, Dr. Lynch was elected as a Fellow to the Arctic Institute of North America in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of polar and subpolar regions. And since 1996 his biography has been included in Canada’s Who’s Who.

thanks for the indepth report & photos of reptiles. I found it very interesting & enjoyed it very much.

Hi Marlyn. Thanks for the kind words. I have always been a sucker for the “creepy-crawlies” of the world. I find them as interesting as birds and mammals but they usually get much less attention.

Wayne